Gabriela Calderon de Burgos and Marcos Falcone

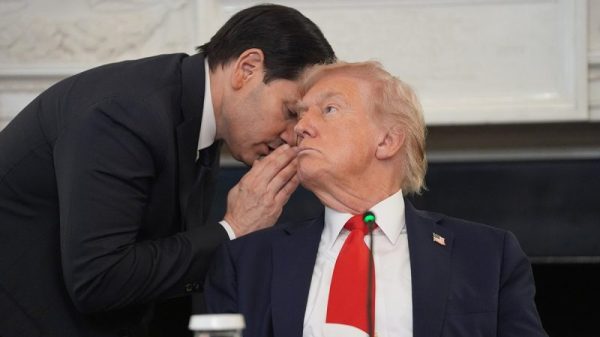

On October 9, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent announced that the US has bought Argentine pesos and finalized a $20 billion currency swap framework with the country’s Central Bank (BCRA). The specifics of the swap, along with forms of assistance the Trump administration has indicated it is ready to provide to support the Milei administration, are expected to be announced on October 14 as the Argentine president meets with President Trump in Washington.

As Bloomberg reported, “Trump and Bessent are making a bet on a nation that’s defaulted and devalued repeatedly over the past several decades. The goal is to help their political ally, President Javier Milei, notch a win in the Oct. 26 midterm elections, and calm markets unsettled by fears of his leftist rivals returning to power.”

This unusual direct intervention from the US Treasury followed the Argentine Treasury’s spending of at least $1.5 billion over the past week in an attempt to stabilize the peso, which continued to lose value nonetheless. Unfortunately, peso volatility has long been the norm in Argentina, rather than the exception. Major peso collapses have occurred in 1952, 1958, 1967, 1975, 1985, 1989, 2001, and 2018/19.

That exchange-rate volatility has often been linked to political events, but it also stems from the Argentine political class’s perennial attempt to control what is arguably the most important price in the economy: the exchange rate between the peso and the US dollar. But the link, which turns political instability into currency instability, need not exist.

In fact, that problem has a solution that also happens to be a better way for the United States to help Argentina. The US could—and should—endorse Milei’s central campaign promise, which he has not yet fulfilled: adopt the United States dollar as the country’s legal tender. In other words, Argentina should dollarize.

To facilitate the process, the peso may still exist, but there would be no new monetary creation, and forced tender would be forbidden. That is, no one shall be forced to accept any currency that does not inspire their trust. In the end, this would mean recognizing the result of the de facto “currency competition” that has taken place in the country over decades and protecting, from now on, Argentines’ freedom to choose the money they use.

President Milei originally promised to dollarize Argentina’s economy back in the 2023 electoral campaign. One of the reasons he thought this was necessary was because the peso is a source of instability. Today, simply by virtue of the peso’s existence, Argentina continues to suffer from exchange rate volatility despite the impressive fiscal discipline and regulatory reforms under Milei’s government. After inheriting a recessionary economy headed toward further collapse—with 211 percent annual inflation and a quasi-fiscal deficit of 15 percent of GDP—the Milei administration has managed to produce a fiscal primary surplus, reduce inflation to below 35 percent, restore economic growth (estimated at between 4.7 and 5.5 percent for 2025), and has even begun numerous deregulations across many sectors of the economy.

What is needed to dollarize? There are no preconditions other than having the people’s support, which Argentines have clearly expressed in the market. According to the latest estimate, Argentines hold $245 billion outside the financial system (or 38 percent of GDP). Besides holding plenty of dollars, Argentines have long been accustomed to carrying out major transactions in US dollars. It is common, for example, for the purchase of an apartment in Buenos Aires to be paid for in US dollars—and in cash.

As economists Steve Hanke and Francisco Zalles explained last year, the process of dollarization simply involves redenominating —with the stroke of a pen—all peso assets and liabilities into US dollars, while simultaneously exchanging the outstanding peso notes and coins in circulation.

Would dollarization require having a large amount of US dollar reserves, as many economists assume? Not really. Emilio Ocampo points out that, as of September 19, and at the then-official exchange rate, the amount needed for the exchange of the currency in circulation was equivalent to $15 billion, or 2.2 percent of GDP.

This exchange of pesos for dollars, at a fixed exchange rate announced on Day 1 of the dollarization process, does not need to happen overnight, as the experiences of other dollarized countries have shown. In Ecuador, the process took nine months, following a government-announced deadline, while in El Salvador it lasted about two years and had no deadline at all.

How could the Milei administration find out the rate at which all accounts and pesos should be converted? No one truly knows the “correct” exchange rate between the peso and the US dollar until a genuinely free market in foreign exchange exists with no capital controls. However, amid current market turbulence, Milei would do well to follow Ecuador’s example: dollarize at or somewhat above the closest indicator to a free-market rate—which, in Argentina’s case, is none other than the black market or “blue dollar” rate.

All liabilities of the Central Bank and the Argentine Treasury are ultimately liabilities of the Argentine state, which must honor them regardless of what currency Argentines recognize as legal tender. What is puzzling is why some Argentine economists—so accustomed to debt defaults and restructurings—imagine that these liabilities suddenly come due on the first day of dollarization. If anything, dollarization would enhance the government’s capacity to meet those obligations, since from Day 1 it would begin collecting taxes in US dollars, a currency that does not lose value nearly as quickly as the peso.

One of the main advantages of dollarization is also one of its prime virtues: it erects a barrier between national politics and the value of the money that people use. Indeed, Ocampo and Nicolás Cachanosky estimate that “on average, a 10.8% change in the probability of a populist regime returning to power causes a 10% depreciation,” a problem that would be eliminated through dollarization. In Ecuador, after a quarter century of dollarization, the economy has withstood substantial political volatility and a decade (2007–2017) of authoritarian rule under Rafael Correa—a member of the so-called Socialists of the 21st Century—who inflicted significant damage on public finances and growth. Yet, there has been no banking crisis; inflation has remained in the single digits for more than two decades, and the financial system is now more developed than Argentina’s.

By dollarizing, no future government would be able to manipulate the exchange rate for electoral purposes so as to make a run against the peso more likely, as has often been the case in Argentina.

Every run on the peso hurts Milei and his free-market agenda. The US financial rescue may prove to be a short-term solution, but it does not address the underlying problem that causes currency instability in the way dollarization does. The longer Milei waits to dollarize, the costlier the delay will become for the people, who could see their peso holdings lose value unnecessarily—and the more Milei risks in the face of possible electoral gains by the opposition, or even the mere expectation of such now or anytime in the future.

Since Argentina, the country whose citizens hold the most physical dollars per capita in the world, is already de facto dollarized, Milei should fulfill his campaign promise and make that reality official.