Romina Boccia and Ivane Nachkebia

Last Tuesday, President Trump said he is looking “very seriously” at the compulsory Australian retirement savings program, which former Prime Minister Julia Gillard has called “our trillion dollar sovereign wealth fund.” While President Trump offered no details about what he finds so attractive about “AustralianSuper,” Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent gave possible indications that the administration is less concerned about reducing unsustainable entitlement obligations and more drawn to the financial predictability that compulsory contributions by Australian employers on behalf of millions of workers provide for the fund.

At the Superannuation Investment Summit in February 2025, Bessent said he “was struck by the confidence you have in the growth. It’s not what one might expect for Australia.… Any other sovereign wealth funds … the volumes are dependent on a particular commodity price—whereas your regularity, sustainability and trajectory are really preferable.”

Turns out, forced contributions collected from workers’ wages are a much more stable source of investment fund income than revenues from inherently volatile commodities that fluctuate with market prices. American workers, beware: The government may be coming for more of our earnings.

There are four possible pathways an Australian-inspired retirement policy could take:

- Replacing Social Security with mandatory individual retirement accounts and a means-tested benefit. (Unlikely due to high transition costs.)

- Diverting a portion of payroll taxes into individual retirement accounts. (Unlikely because Social Security is already running cash-flow deficits.)

- Adding mandatory retirement contributions on top of Social Security payroll taxes to establish a quasi “sovereign wealth fund.” (More likely as there is an unholy alliance of financial service firms who would stand to profit, and paternalist do-gooders who believe Americans should be forced to save more for retirement. This could be done through a “hidden” tax increase by increasing employer contributions.)

- Establishing a US sovereign wealth fund with borrowed money. (Even more likely, as borrowing money to play the markets doesn’t create any immediate losers and presents even more of a hidden tax increase by adding to the burden confronted by younger, future taxpayers, while claiming that investment returns will more than offset the initial reduction in the US fiscal position.)

Other than the first approach, which would convert a pay-as-you-go, unsustainable entitlement program into a compulsory, defined contribution plan with an antipoverty backstop, none of these possible approaches should excite those who believe in limited government. Workers don’t need Washington to seize a bigger share of their earnings to “help” them save. The real risk here is a politicized sovereign wealth fund that expands governmental influence over markets.

The Australian Model

Australia’s Superannuation Guarantee (SG) is a compulsory savings system that requires employers to pay 12 percent of employee wages into individual retirement accounts. Workers can choose from various investment funds that invest in assets including stocks, bonds, and private companies. The government generally restricts withdrawals from these accounts until the age of 60. Alongside this compulsory savings program, the Australian retirement system includes the Age Pension, an antipoverty benefit means-tested against both income (including superannuation income) and assets.

Compulsory SG’s economic costs are borne mostly by employees—indirectly through reduced employment opportunities and directly through lower take-home pay. As Australian economist Stephen Kirchner has noted, some voters fail to recognize these costs, providing a convenient tool for politicians: When the government-provided Age Pension faces fiscal pressures, it’s easier to raise SG’s mandatory contributions to reduce or eliminate future public benefit costs by increasing private retirement incomes that trigger means-testing than to reform the underlying benefit. Australia has already increased mandatory contributions significantly, from 9 percent to 12 percent between 2013 and 2025.

Kirchner also notes that higher-income households tend to offset forced SG contributions by reducing voluntary saving or borrowing more to smooth consumption. For lower-income households, SG crowds out saving for other priorities such as housing. While SG may raise overall savings among low-income households, it does so for the wrong reasons: As these households have more limited borrowing capacity, they are unable to fully offset the forced contributions the way higher-income households can. “Ironically … compulsory super succeeds in raising household and national saving largely by exploiting the financial constraints experienced by low-income households,” explains Kirchner. Estimates of the voluntary savings offset range from 17 to 75 cents for every dollar of compulsory SG contribution.

Politicians may find compulsory savings attractive if it lets them avoid confronting unsustainable retirement promises. The political path of least resistance becomes forcing workers to contribute more—not making the system solvent by reducing public benefits.

Adding Mandatory Contributions on Top of Social Security Is a Bad Idea

Replacing Social Security with the Australian model of compulsory savings and a means-tested benefit would be an improvement over the current pay-as-you-go model by empowering workers with ownership over their forced contributions. The catch is that doing so now would entail massive transition costs. Instead, President Trump might be considering mandatory retirement savings on top of Social Security—an idea floated by BlackRock’s CEO, Larry Fink. But forcing workers to give up more of their paychecks, in addition to the 12.4 percent payroll tax, would be a misguided policy.

Americans are already successfully utilizing voluntary plans like 401(k)s, with 56 percent of workers participating in an employer-based plan. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), voluntary retirement plans in the United States will replace 34 percent of lifetime earnings for young workers, the highest among member nations. This strong voluntary component is the reason the US retirement system is projected to deliver a 73 percent lifetime earnings replacement, compared with the OECD average of 55 percent.

Looking at broader savings patterns, Federal Reserve data show that, in 2022, the median net worth of seniors aged 65–74 was $410,000, compared with $136,000 for those aged 35–44 and $247,000 for those aged 45–54. This demonstrates that Americans are accumulating meaningful assets over their working lives without the need for compulsory savings.

Compelling American workers to save on top of existing payroll taxes would displace voluntary savings and disproportionally harm low-income workers. A superior alternative would be to introduce universal savings accounts (USAs), which would expand opportunities for voluntary saving. Unlike existing voluntary retirement accounts, USAs wouldn’t lock away workers’ savings until retirement, allowing for penalty-free withdrawals at any time, for any purpose. This flexibility would be especially attractive for younger and lower-income workers, allowing them to save according to their own preferences—for emergencies, to boost their education, purchase a home or car, and any other immediate needs—without facing tax penalties.

Diverting Payroll Taxes into Individual Accounts Would Explode Federal Debt

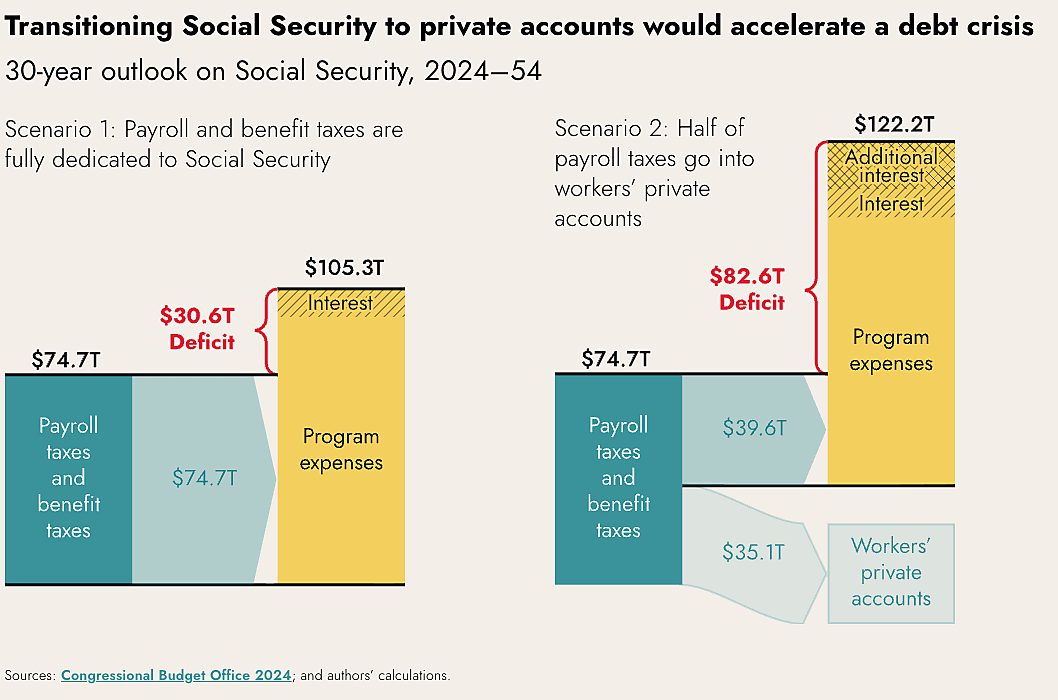

The Trump administration could be considering diverting a portion of payroll taxes into individual accounts rather than mandating additional savings. While this option was attractive during President George W. Bush’s presidency, it would be fiscally detrimental today. As we have calculated before, diverting half of payroll taxes into individual accounts would increase Social Security’s 30-year shortfall by $50 trillion (see chart below), exacerbating the already-dismal fiscal outlook and accelerating a debt crisis.

The Cassidy-Kaine Social Security Plan Is a Risky Bet with Taxpayer Money

Earlier this year, Senators Bill Cassidy (R‑LA) and Tim Kaine (D‑VA) outlined a plan to establish a “sovereign wealth fund” to help cover Social Security’s long-term shortfall. Under this proposal, the government would borrow $1.5 trillion up front and invest in the stock market, allowing the investment to grow for 75 years. During that period, the Treasury would continue covering Social Security’s cash-flow deficits. After 75 years, the investment gains, net of the interest costs on the borrowed $1.5 trillion, would be used to repay the Treasury.

This strategy is essentially a risky bet that long-run stock market returns will exceed the interest on federal debt. The risks are even greater if no meaningful Social Security reforms are adopted during the 75-year period Treasury carries the program’s costs—an obligation equal to roughly $28 trillion in present value terms. Such additional borrowing could lead bond markets to demand higher interest rates, further reducing the likelihood that this strategy would work. And if the bet failed, taxpayers would bear the loss.

Moreover, this proposal isn’t even a sovereign wealth fund but a “pension obligation bond,” which doesn’t build new wealth but redistributes it from current stock owners (Americans and global investors) to the federal government. Large-scale government purchases of stocks would also lower future stock returns, functioning as an implicit tax on Americans’ savings.

The Cassidy-Kaine plan is arguably the most likely among the four scenarios because it is politically convenient: It avoids imposing immediate, visible costs on voters while shifting burdens and risks to younger, future taxpayers.

But regardless of the specific model the president has in mind, an additional problem is how Americans’ contributions—or borrowed funds—would be invested. Under the Cassidy-Kaine proposal, the federal government would own roughly a third of the US stock market after 75 years. As Boccia has written, this “could bring the US economy closer to a form of state ownership—something Americans should resist.”

If the chosen approach involves individual retirement accounts, would workers choose from many competing funds, as in Australia? If so, would the government interfere in their investment decisions, perhaps requiring portfolios to include a certain share of Treasury bonds or politically favored industries? Or would the contributions be invested in a single government-controlled sovereign wealth fund, a recipe for political meddling and misguided investments?

If the president wants to look Down Under for retirement-reform inspiration, he should look to New Zealand, not Australia. New Zealand provides a predictable, flat benefit to all retirees through New Zealand Superannuation, which is an effective way to alleviate senior poverty at relatively low cost. Workers are automatically enrolled in the KiwiSaver retirement plan but may opt out, unlike Australia’s superannuation program.

Depending on the flat-benefit level and eligibility rules, a similar model in the United States could eliminate Social Security’s funding shortfall and ultimately reduce payroll taxes, freeing up even more resources for voluntary saving.

You can read more about the New Zealand model and why a transition to a similar approach makes sense in our new book, Reimagining Social Security: Global Lessons for Retirement Policy Changes.

Overall, none of the plausible interpretations of President Trump’s comments point toward a desirable path. The idea of Australian-style retirement accounts, regardless of the specific design, joins a growing list of recent proposals that sidestep Social Security’s core problems and offer politically convenient alternatives to meaningful reform. The reality is that we’re closing yet another year without progress on Social Security—in fact, with regress—and every year of inaction ultimately allows Social Security’s financial problems to compound, raising the eventual economic and fiscal costs for workers and retirees alike.