Alex Nowrasteh and Ryan Bourne

The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is the biggest domestic policy news of 2025 so far. Established by executive order (EO) on January 20, 2025, and “led” by Elon Musk, DOGE officially occupies the administrative shell of the US Digital Service and was mandated to “implement the President’s DOGE Agenda, by modernizing Federal technology and software to maximize governmental efficiency and productivity.” However, DOGE’s reach clearly extends far beyond this, with an impact across the federal government that has seemed chaotic. As a result, observers struggle to develop a coherent model to explain DOGE’s actions and predict its future behavior.

This is unsurprising given DOGE’s changing missions. Upon conception before the election, Musk said DOGE would aim to cut $2 trillion in spending to balance the budget. This was a remit we enthusiastically embraced with our 2024 Cato report that detailed where and how to cut that amount and potentially much more depending on willingness to reform entitlements. Musk and his then-partner Vivek Ramaswamy subsequently wrote that DOGE would harness executive actions to reduce the administrative state, cheapen the procurement process, reduce the civil service, and reform other aspects of government, including on the regulatory front.

DOGE’s goals changed somewhat again upon DOGE’s creation when Musk revised his stated goal to cut $1 trillion of spending. Then, Trump’s EOs of January 20th empowered DOGE to reduce the federal workforce and overhaul the government’s technology. Later EOs focused DOGE on downsizing the federal workforce, eliminating specific small bureaucracies, and rescinding or modifying unlawful or burdensome regulations.

Since its creation, DOGE has pursued aspects of all the above goals, emphasizing publicly ways that it has reduced spending by firing government employees and canceling contracts.

Successfully affecting DOGE’s behavior from the outside requires understanding, at least somewhat, its goals and how it functions. This abridged history of its shifting mission doesn’t tell us where DOGE is headed, nor does it explain why it has behaved in the way it has to this point. Others have struggled with explaining DOGE. Santi Ruiz, for instance, has many insightful observations, but he doesn’t have a coherent model or set of models for interpreting its actions. Below are six theoretical models for understanding DOGE’s action to date, each with supporting evidence.

- DOGE is seeking to purge progressive influence within the federal government.

DOGE is systematically eliminating left-leaning personnel, policies, symbols, and government funding for progressive nonprofits and causes within the federal government—and will continue to do so. DOGE’s broad exemption of more conservative-leaning security agencies from review except for reevaluating all consulting contracts, its focus on dismantling DEI programs, and its termination of probationary employees hired under the Biden administration are evidence for this. Foreign aid is certainly perceived as progressive-coded, which explains why DOGE initially targeted USAID—an agency known for funding numerous left-leaning nonprofits and international NGOs. DOGE’s other recent target is the Department of Education, the source of many insidious progressive DEI programs and other policies that conservatives rightly abhor. It’s even going after progressive symbols such as the Anthony Fauci exhibit at the National Institutes of Health. He is a popular progressive icon despised by conservatives as the personification of progressive control over the government-funded public health sector. This is primarily a theory of what agencies DOGE decides to prioritize cutting.

- DOGE is a scaled-up public version of Musk’s style of corporate restructuring applied to the federal government.

DOGE is applying Musk’s cost-cutting playbook to the federal government by prioritizing workforce reductions. Musk applied such a strategy to Twitter when he acquired it, as explained in Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography and elsewhere. Musk likes to delete steps or people involved in a production process to streamline it, but his rule of thumb is, “If you’re not adding things back in at least 10 percent of the time, you’re clearly not deleting enough.” This model explains why the government sought to rehire nuclear staff after DOGE fired them. Rather than a failure, rehiring workers is an expected part of Musk’s downsizing process.

Federal workforce reductions are necessary, but they will have less of a positive budgetary effect on the federal government than for private firms where payroll costs are often more than 40 percent of revenue for professional services firms. According to our colleague Chris Edwards, total compensation for the 3.8 million federal defense and nondefense workers accounts for only 8 percent of spending (excluding postal employees). The federal government’s labor costs are lower than those of private firms because its primary task is transferring money from taxpayers to beneficiaries, which is not a labor-intensive activity, whereas businesses typically make profits by supplying goods and services that are more labor-intensive.

While there are undoubtedly many government employees who can be terminated, broad and indiscriminate layoffs in the absence of broader regulatory reform can prove false economies. Much of federal regulatory activity is enforcement of existing rules, which should be slashed. However, other federal personnel approve permits for private actions like oil drilling on federal lands, which are required by statutes implemented through regulations. Firing personnel whose jobs are to approve permits halts new drilling activity so long as the underlying laws and regulations are unaffected, thus reducing overall economic efficiency. Alex Tabarrok is similarly concerned about the indiscriminate firing of employees at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which could lengthen drug review times. Personnel cuts may also delay deregulatory actions the administration has ordered agencies to pursue. If the personnel cuts were combined with Ramaswamy’s DOGE strategy to focus on reducing the regulatory and administrative state, then across-the-board firings would have been less disruptive to the private economy. As we’ve noted before, absent reducing the federal government’s size and scope, its disparate range of objectives can create inherent efficiencies that staff layoffs can exacerbate.

Still, this shouldn’t come across as too negative. It’s easy to nitpick and ignore the forest for the trees. While the drilling example, the FDA, and possible cuts to workers tasked with deregulating other sectors of the economy are negative, they are set against many other positive firings at the Departments of Health and Human Services, Education, USAID, and elsewhere. Regardless, the scale and scope of firings are consistent with a Musk-style restructuring that sometimes goes too far, and that can be later corrected with rehiring. This is primarily a theory of how DOGE cuts budgets in the agencies it targets.

- DOGE is the first step of a public relations campaign to build popular support for spending cuts.

Eliminating waste, fraud, and abuse is an often repeated justification for DOGE. Its first target was unpopular foreign aid dispensed through USAID. DOGE’s early announcements highlighted a cut of $50 million for “condoms for Hamas” that turned out to be contraceptive aid for a province in Mozambique named Gaza. Condoms for Hamas would have certainly been ludicrous, actual contraceptive aid for Mozambique somewhat less so. Nevertheless, many Americans will rightly think that is not a priority use of their taxpayer dollars.

Still, DOGE has canceled several small-dollar projects that are just as silly, such as a Peruvian comic book about an education superhero that had to feature an LGBTQ+ character to address mental health issues. Often, the money was already spent, but at least it sends the signal there won’t be any more spending on these or similar initiatives. DOGE’s efforts to reduce spending on more popular programs like Social Security are stopped cold, such as its scrapped proposal to reduce phone services for program beneficiaries. The goal of reducing waste, fraud, and abuse is also inconsistent with the administration’s firing of Inspectors General whose jobs were to monitor federal actions to reduce, among other things, waste, fraud, and abuse.

Still, the focus on ludicrous, silly, and absurd spending on unpopular programs like foreign aid may be the first part of a strategy to push a desperately needed austerity agenda focused on the actual programs eating the budget. As OMB director Russ Vought has said:

When families decide to get on a budget, they do not target the largest and immovable items of their spending, like their mortgage, first. They aim to restrain discretionary spending—they eat out less, shop less, and find cheaper ways of entertaining themselves. Then they look at what makes sense for the immovables—how to refinance their debt or make major life changes. Politically, a similar approach is the only way the American people will ever accept major changes to mandatory spending. They are simply not going to buy the notion that their earned entitlements must be tweaked while the federal government is funding Bob Dylan statues in Mozambique or gay pride parades in Prague. This Budget mathematically must include substantial reforms to mandatory spending to achieve balance—although importantly, there are no benefit reductions to Social Security or Medicare beneficiaries—strategically, it will emphasize the discretionary cuts needed to save the country from tyranny.

- DOGE is an essential component of a Trump administration legal challenge to expand the president’s power of impoundment.

DOGE is testing the limits of presidential control over federal spending, potentially setting the stage for court cases and a Supreme Court ruling that increases the president’s power of impoundment. There are a staggering number of lawsuits filed against the Trump administration’s actions and several are challenging DOGE’s cuts. Beyond DOGE, OMB Director Russ Vought and President Trump claim the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 is unconstitutional and the president has enormous authority to impound spending. Our colleague Gene Healy notes that “historically, there’s been little support for [their] view event among conservative legal heavyweights.” Regardless, DOGE could be an important component of a legal strategy to convince the Supreme Court to change its mind on the constitutionality of a broader presidential power over impoundment and to make a head start in cutting spending in case these efforts are successful.

- DOGE provides political cover for Congress to be even more fiscally irresponsible.

Congressional Republicans could be politically free-riding on DOGE, using it as a way to extend and enhance the 2017 tax cuts without making significant budget cuts—claiming that DOGE will handle federal spending. Cato’s Director of Budget and Entitlement Policy Romina Boccia noted that, “The House recently passed a budget resolution calling for $4.5 trillion in tax cuts plus $300 billion in new spending over the coming decade—all balanced out with $2 trillion in offsetting spending cuts and about $2.6 trillion in pixie dust from assuming their budget will have economic growth taking off like one of SpaceX’s rockets.” All this is playing out while Congress, other politicians around the country, and the public focus on DOGE. Media and political hyperventilation about “large scale” and “massive” cuts as well as DOGE’s own exaggerations of the scale of its austerity could certainly help Congress shirk its fiscal responsibility yet again.

- DOGE is about self-interest and cronyism.

DOGE isn’t about cutting government waste—it’s about consolidating business power for friends, punishing competitors, and securing lucrative opportunities for DOGE and other tech bro insiders via future government contracts and privileges. This theory, pushed mainly by progressives, highlights DOGE operatives gaining access to federal payment systems and procurement contract details, allowing those close to Elon Musk and friends to obtain sensitive information about competitors to his companies.

While DOGE has acted more broadly than in departments or agencies that Musk’s businesses are involved with, there have been examples of conflicts of interest. FDA employees reviewing Neuralink, Musk’s controversial brain-chip company, were reportedly fired (with some later rehired). The FAA, which has clashed with SpaceX over launch delays and environmental reviews, has been another target and Musk has criticized a competitor of his own company, Starlink, that provides services to the FAA. The recent image of President Trump doing marketing for Tesla on the front lawn of the White House, the controversy about the State Department’s apparent plans to purchase Tesla cybertrucks, and the Trump administration’s intentions to establish a strategic crypto reserve provide further evidence of a culture of crony capitalism, which DOGE is seen as part of.

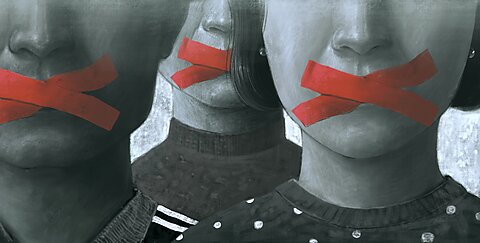

This theory says that DOGE’s other activity is a smokescreen for more self-interested intentions on behalf of its members and backers. The time-limited nature of DOGE and lack of transparency around its leadership and structure is seen as further evidence that something underhand is at play.

Many of the models above help to explain the outwardly chaotic nature of DOGE’s actions. Horror at the resulting chaos is one reason why some advocates of smaller government recoil at DOGE. “Cut the government,” some of them would say, “but not like this!” To be sure, there are more orderly ways to reduce the size and scope of the federal government and there are legitimate and important legal and constitutional concerns about DOGE. Still, any reduction in the size and scope of an organization that spends approximately $7 trillion annually will be chaotic.

The government was built and expanded over centuries and is a complex bureaucracy of overlapping responsibilities, powers, and controls with its own diverse and evolved internal operations and local tacit knowledge inscrutable to outsiders. Firm bankruptcies and downsizings are often chaotic and disorderly, so Americans should only expect more such chaos from the substantially larger federal government that is involved in virtually every aspect of American life.

It’s tricky to make accounting comparisons between the federal government and private firms, but Walmart’s operating expenses in 2024 were about $621 billion—less than one-tenth of the federal government’s outlays that year. Walmart would certainly be thrown into chaos if it sought to reduce its costs through bankruptcy proceedings or substantial layoffs. Supporters of smaller government should be tolerant of short-term disruption so long as we think that DOGE can advance the goal of a smaller and less intrusive federal government and that Congress will ultimately do what’s necessary to entrench the reforms and savings.

Social science models simplify reality, spotlighting key variables that may shape DOGE’s actions in a way that can be tested. The models discussed above clearly simplify the complex endeavor of reforming the largest human organization ever by expenditures—the US federal government. They help explain past decisions and anticipate future moves. The models above try to make sense of DOGE’s actions so far. They are not mutually exclusive, yet several can be informative together or alone, while some may only make sense temporarily. Other models not set out here might offer fresh insights, but scholars should try to develop them. Without doing so, one of the biggest policy initiatives of President Trump’s second term risks being under-analyzed or misunderstood.